Did U.S. Admiral Harry E. Yarnell actually plan the attack on Pearl Harbor?

I had always thought that Admiral Yamamoto and the Imperial Japanese Navy had planned their attack based upon the success of the Royal Navy’s carrier-based attack on the main Italian Naval Base at the harbor of Taranto, Italy in 1940. That has been the conventional wisdom expressed by several naval historians in recent books. I was not aware until recently of the following intriguing bit of history.

|

| ADM Harry E. Yarnell Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet |

The following article appeared in the July/August issue of American Heritage.

February 7, 1932--A date that would live in...amnesia.

By Thomas Fleming.

On February 1, 1932, the United States began its annual Grand Joint Army and Navy Exercises. As in earlier years, the participating soldiers and sailors were divided into "Blue" and "Black" teams. This year the goal was to test the defenses of the main American bastion in the Pacific. The Blue attackers, with the Navy's two new carriers, USS Saratoga and Lexington, plus a formidable array of battleships and cruisers, were ordered to land a combined Army-Marine assault force on Oahu, Hawaii. The Black defenders, equally well supplied with battleships and cruisers and submarines, were supposed to stop them. The Blacks also had imposing batteries of antiaircraft guns and more than 100 planes at their disposal. For a decade, the Navy had been evolving Plan Orange, which envisioned a war between the United States and Japan.

By 1932 the Japanese had the third strongest navy in the world, surpassed only by those of the United States and Great Britain. Already, Japan's diplomats were dropping hints that the country resented the restrictions imposed by the arms-limitation treaties of the 1920s and planned to insist on absolute parity in the upcoming naval talks in London. The Navy knew surprise attack was one of Japan's fundamental strategies. The Japanese had begun their war with Russia in 1904 with a devastating strike on Port Arthur that annihilated the Russian Asiatic Fleet. As the joint exercises got under way, the Blue force sent its two carriers and four destroyers ranging ahead of its battleships and cruisers, under the command of Rear Adm. Harry E. Yarnell. A blunt, salty 57-year-old from Independence, Iowa, Yarnell was one of the few American admirals with an avid interest in airpower. He had learned to fly in the 1920s and had commanded the USS Saratoga when she was launched in 1927. The plans for the Grand Exercises called for the Saratoga and Lexington to make an air attack on Hawaii, but everyone assumed the carriers would be detected and "sunk" by submarines or land-based planes long before they could get close enough-roughly 100 miles-to launch their planes. Yarnell had other ideas. To evade Black patrol planes, he led his task force to a stretch of ocean, northeast of Oahu, where rain, squally winds, and lowering clouds were abundant in the winter. He also knew that the prevailing northeast wind sent this dirty weather swirling over Oahu to dump its moisture on the 2,800-foot-high Koolau range, which overlooked Pearl Harbor. Not only was there a good chance that his ships could maneuver off Oahu undetected, but, once they launched their planes, the pilots could roar through the rain clouds and burst into clear, sunny weather over Pearl Harbor. The canny Yarnell decided to add one more touch to his plan. He would attack early on a Sunday morning.

At nightfall on February 6, 1932, Yarnell's Blue task force was plowing through heavy seas 60 miles northeast of Oahu. The ships were running with no lights, under absolute radio silence. In the predawn murk on Sunday, February 7 (Editorial note: As most will recall the Japanese attack occurred on Sunday December 7, 1941), with the seas still mountainous, Yarnell launched 152 planes from the Saratoga and the Lexington. It was a daring gamble, sending the biplanes of the day aloft from the bucking, rolling carriers, but not a plane was lost. An hour later, Yarnell's fliers came out of the clouds shrouding the Koolau Range, and there lay Pearl Harbor below them in the sunshine, getting ready for a peaceful Sunday.

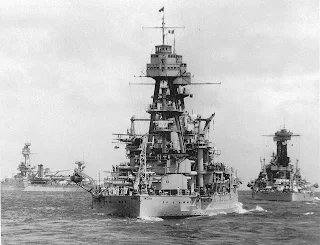

|

| USS Arizona BB-39, Flagship of Battleship Division 1 US Pacific Fleet circa 1939 |

Yarnell's fighters "strafed" lines of planes parked on runways, while his dive-bombers dumped 20 tons of theoretical explosives on airfields, ships in the anchorage, and Army headquarters at Fort Shafter. Not a single fighter rose to oppose them. The New York Times correspondent covering the Grand Exercises reported that the Blue planes "made the attack unopposed by the defense, which was caught virtually napping, and [they] escaped to the mother ships without the slightest damage being inflicted on them." He also noted that the Black defenders had yet to locate the Blue fleet 24 hours after the attack. The Black commanders put up a vigorous defense-after the fact. They persuaded the umpires to rule that 45 of Yarnell's planes had been hit by antiaircraft fire. They also pointed out that their battleships were at sea when Yarnell attacked and insisted that in a real war they would have soon caught up with his carriers and massacred them with their long-range guns. A few air-minded admirals, including the outspoken Yarnell, argued that his Blue attackers had won a stunning victory that demanded a re-evaluation of American naval tactics. But the battleship admirals, a comfortable majority, quickly voted them down. In the end, the final report of the Grand Exercises' umpires made no reference whatsoever to Yarnell's Sunday-morning raid. On the contrary, the umpires concluded: "it is doubtful if air attacks can be launched against Oahu in the face of strong defensive aviation without subjecting the attacking carriers to the danger of material damage and consequent great losses in the attack air force." Although the U.S. Navy refused to pay attention, the Japanese paid close attention to a potential enemy's naval maneuvers, and their observers forwarded a thorough report of Yarnell's exploit to Tokyo. In 1936 Japan's Navy War College circulated a monograph, Study of Strategy and Tactics in Operations Against the United States. One of its principal conclusions was: "in case the enemy's main fleet is berthed at Pearl Harbor, the idea should be to open hostilities by surprise attack from the air." The next year, Japan declared war on China. The admiral in command of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet was Harry Yarnell. He was bitter about his assignment to what was known in the Navy of that time as "the small fleet." The admiral was paying the price for his outspoken advocacy of airpower. Admiral Yamell repeatedly urged the United States to take a stronger stand against Japanese aggression. He was ignored, as he had been when he spoke out for airpower. Between 1936 and 1940, the Navy laid keels for 12 battleships and only one aircraft carrier. In 1939 Harry Yarnell retired, a baffled, disappointed man.

So, on another Sunday almost a decade later, another carrier task force, undetected beneath thick clouds, operating under radio silence, plowed through heavy seas northeast of Hawaii. This time, Admiral Yarnell's colleagues would get the point.

The following photograph is of IJS Zuikaku, WWII Japanese Navy aircraft carrier of the Shokaku Class. One of the six aircraft carriers whose planes struck Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941. Below the photo is a reprint of a page from the United States Navy Office of Naval Intelligence Manual ONI 41-42, giving contemporary known information on the Shokaku Class carriers, circa 1942.

The following photograph is of IJS Zuikaku, WWII Japanese Navy aircraft carrier of the Shokaku Class. One of the six aircraft carriers whose planes struck Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941. Below the photo is a reprint of a page from the United States Navy Office of Naval Intelligence Manual ONI 41-42, giving contemporary known information on the Shokaku Class carriers, circa 1942.

The USS Arizona BB-39 was the sister ship to the lead in the class the USS Pennsylvania BB-38. Initially built in 1910's, both battleships underwent an extensive modernization in the early 1930's. Along with the USS Nevada BB-36, they comprised Battleship Division 1 of the United States Navy's Pacific Fleet at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

|

| USS Arizona BB-39 working in heavy seas in the 1930's |

|

| USS Arizona BB-39 maneuvering in column formation line astern in company with two other battleships |

|

| Plan views of the USS Arizona BB-39 showing details of battle damage inflicted |

|

| Elevation of the USS Arizona BB-39 resting on the harbor floor, Pearl Harbor, Ford Island, Hawaii |

The New York Times reported on the exercise, noting the defenders were unable to find the attacking fleet even after 24 hours had passed. U.S. intelligence knew Japanese writers had reported on the exercise. Ironically, in the U.S., the battleship admirals voted down a reassessment of naval tactics. The umpire's report did not even mention the stunning success of Yarnell's exercise. Instead they wrote, "It is doubtful if air attacks can be launched against Oahu in the face of strong defensive aviation without subjecting the attacking carriers to the danger of material damage and consequent great losses in the attack air force." The United States Navy had to wait until the Battle of Midway in June 1942 in order to achieve that objective.

There is a very interesting post-script to this story regarding an assessment made by then ADM (later FLT ADM) Chester A. Nimitz.

An interesting story about the insight Admiral Nimitz had into the "Mistakes" the Japanese made when they bombed Pearl Harbor.

Tour boats ferry people out to the USS Arizona Memorial in Hawaii every thirty minutes. We just missed a ferry and had to wait thirty minutes. I went into a small gift shop to kill time. In the gift shop, I purchased a small book entitled, "Reflections on Pearl Harbor" by Admiral Chester Nimitz.

Sunday, December 7th, 1941--Admiral Chester Nimitz was attending a concert in Washington D.C. He was paged and told there was a phone call for him. When he answered the phone, it was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on the phone. He told Admiral Nimitz that he (Nimitz) would now be the Commander of the Pacific Fleet.

Admiral Nimitz flew to Hawaii to assume command of the Pacific Fleet, landing at Pearl Harbor on Christmas Eve, 1941. There was such a spirit of despair, dejection and defeat--you would have thought the Japanese had already won the war.

On Christmas Day, 1941, Adm. Nimitz was given a boat tour of the destruction wrought on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. Big sunken battleships and navy vessels cluttered the waters every where you looked. As the tour boat returned to dock, the young helmsman of the boat asked, "Well Admiral, what do you think after seeing all this destruction?" Admiral Nimitz's reply shocked everyone within the sound of his voice. Admiral Nimitz said, "The Japanese made three of the biggest mistakes an attack force could ever make or God was taking care of America. Which do you think it was?" Shocked and surprised, the young helmsman asked, "What do you mean by saying the Japanese made the three biggest mistakes an attack force ever made?"

Nimitz explained. Mistake number one: the Japanese attacked on Sunday morning. Nine out of every ten crewmen of those ships were ashore on leave. If those same ships had been lured to sea and been sunk--we would have lost 38,000 men instead of 3,800.

Mistake number two: when the Japanese saw all those battleships lined in a row, they got so carried away sinking those battleships, they never once bombed our dry docks opposite those ships. If they had destroyed our dry docks, we would have had to tow everyone of those ships to America to be repaired. As it is now, the ships are in shallow water and can be raised. One tug can pull them over to the dry docks, and we can have them repaired and at sea by the time we could have towed them to America. And I already have crews ashore anxious to man those ships.

Mistake number three: every drop of fuel in the Pacific theater of war is in top of the ground storage tanks five miles away over that hill. One attack plane could have strafed those tanks and destroyed our fuel supply. That's why I say the Japanese made three of the biggest mistakes an attack force could make or God was taking care of America.

|

| U.S. Naval Base, Pearl Harbor, note proximity of the massive fuel tank farm immediately to the left of the main channel and "Battleship Row", October 1941 |

|

| A close-up of the U.S. Navy Submarine Base, Pearl Harbor, better showing the extent of the fuel tank farm, October 1941 |

I've never forgotten what I read in that little book. It is still an inspiration as I reflect upon it. In jest, I might suggest that because Admiral Nimitz was a Texan, born and raised in Fredricksburg, Texas--he was a born optimist. But anyway you look at it--Admiral Nimitz was able to see a silver lining in a situation and circumstance where everyone else saw only despair and defeatism. President Roosevelt had chosen the right man for the right job.

We desperately needed a leader that could see silver linings in the midst of the clouds of dejection, despair and defeat.

There is a reason that our national motto is, IN GOD WE TRUST.