The first recorded use of a crude type of heliograph in military communications is believed to have been by the Athenians, using highly polished shields, between Athens and Marathon, a distance of 26 miles in 490 BC. This was to signal the victory over the Persians, and apparently occurred in parallel with the fabled Greek runner who also conveyed word of the outcome of the battle. This incident in history is recounted by Alan Harfield, author of a book entitled Early Signalling Equipment, THE HELIOGRAPH, A Short History, Royal Corps of Signals Museum, 1986.

|

| An Athenian Hoplon Shield - Possibly one similar could have been the first military 'heliograph' ( Could stand a bit of polishing) circa 400 BC |

|

| The Zulu War - Heliograph at work across the Tugela River 1879 |

|

| 2nd Life Guard Signalers - Heliograph Drill |

The relatively modern military heliograph found its origins in the heliothrope, invented by Karl Gauss, a German scientist and mathematician, in 1821. This ‘light-reflecting’ system evolved to the heliostat, a non-oscillating mirrored instrument, and was converted to a more effective device with the incorporation of a shutter, which facilitated the use of Morse Code. After this evolved system was being used, Henry Mance (later Sir Henry Mance) brought it to the attention of the British Indian Government, and it was introduced into the British Army in 1875. Obviously not in time to provide communications during the Indian Mutiny (1857 – 1858), however it did see extensive service in India, particularly in the Northwest Frontier, well into the Twentieth Century. Given an optimal operational environment heliographs can efficiently operate at a range of up to 70 miles. Heliographs were extensively used for line-of-sight communications in both India and Africa. They were also widely used by the United States Army, particularly in the Southwest desert. The following link details the employment by the United States Army against Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apaches in the 1880's; http://huachuca-www.army.mil/pages/history/Rolak.html.

|

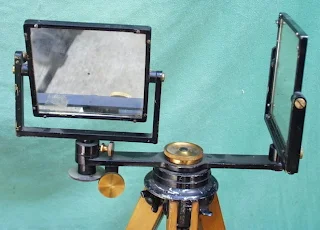

| U.S. Army Portable Heliograph (Mance type) circa 188'0s |

One of the more common configurations of military issued heliographs is the British and Commonwealth Army’s, HELIOGRAPH, 5-inch, Mark V. It was employed into the early part of World War II, and used by the Pakistani Army up to 1975. It is said that the Canadian Army retained theirs in TO&E well into WWII, because officers thought they made “excellent shaving mirrors". Complete heliograph kits can still be found today, however are becoming scarce, necessitating acquisition of multiple units in order to comprise one complete heliograph with its leather carrying case, tripod, duplex mirror assembly, accessories and cased spare mirrors.

As a closing aside Rudyard Kipling wrote one of his more memorable poems, "A Code of Morals" about the ficticious use of the heliograph in the general area of the Khyber Pass, near the Afghan Border of then India.

|

| Shadi Bagiar, entrance to the Khyber Pass circa 1878 |

I merely mention I

Evolved it lately. 'Tis a most

Unmitigated misstatement.

Now Jones had left his new-wed bride to keep his house in order,

And hied away to the Hurrum Hills above the Afghan border,

To sit on a rock with a heliograph; but ere he left he taught

His wife the working of the Code that sets the miles at naught.

And Love had made him very sage, as Nature made her fair;

So Cupid and Apollo linked , per heliograph, the pair.

At dawn, across the Hurrum Hills, he flashed her counsel wise--

At e'en, the dying sunset bore her husband's homilies.

He warned her 'gainst seductive youths in scarlet clad and gold,

As much as 'gainst the blandishments paternal of the old;

But kept his gravest warnings for (hereby the ditty hangs)

That snowy-haired Lothario, Lieutenant-General Bangs.

'Twas General Bangs, with Aide and Staff, who tittupped on the way,

When they beheld a heliograph tempestuously at play.

They thought of Border risings, and of stations sacked and burnt--

So stopped to take the message down--and this is what they learnt--

"Dash dot dot, dot, dot dash, dot dash dot" twice. The General swore.

"Was ever General Officer addressed as 'dear' before?

"'My Love,' i' faith! 'My Duck,' Gadzooks! 'My darling popsy-wop!'

"Spirit of great Lord Wolseley, who is on that mountaintop?"

The artless Aide-de-camp was mute; the gilded Staff were still,

As, dumb with pent-up mirth, they booked that message from the hill;

For clear as summer lightning-flare, the husband's warning ran:--

"Don't dance or ride with General Bangs--a most immoral man."

[At dawn, across the Hurrum Hills, he flashed her counsel wise--

But, howsoever Love be blind, the world at large hath eyes.]

With damnatory dot and dash he heliographed his wife

Some interesting details of the General's private life.

The artless Aide-de-camp was mute, the shining Staff were still,

And red and ever redder grew the General's shaven gill.

And this is what he said at last (his feelings matter not):--

"I think we've tapped a private line. Hi! Threes about there! Trot!"

All honour unto Bangs, for ne'er did Jones thereafter know

By word or act official who read off that helio.

But the tale is on the Frontier, and from Michni to Mooltan

They know the worthy General as "that most immoral man."

So much for the operational security of the heliograph!