On very infrequent occasion this author begs the indulgence of the reader in addressing subjects of a more in-depth and profound nature, far a field from the escape to the subject of toy soldiers.

Amongst the many profound wisdoms of the Chinese general and military strategist Sun Tzu is the saying (variable translations and wording); “Know thy enemy, know thyself. A thousand battles, a thousand victories.”

In a brand-new article in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (February 2020) this wisdom is reiterated in a penetrating discussion by two currently active duty naval intelligence professionals. It particularly struck this author with both its insight and significance. Reflecting in retirement on my dual career as a weapon systems engineer/threat analyst and naval intelligence officer, am able to personally relate the importance of their thesis based upon two specific cases, both of which have been previously related in this blog’s posts;

http://arnhemjim.blogspot.com/2013/04/one-of-don-quixotes-broken-lances_19.html

While the perspective conveyed in those blog posts is much narrower in context than that envisioned by the authors, I think they show the critical importance in conducting threat analysis through quantitively evaluating the interactive engagement of own capabilities with those of the enemy. This total perspective is of particular priority both during the initial design and development of weapon systems, but in their employment, i.e. strategy and tactics, as well.

With both gracious full acknowledgment of their knowledge and insight, as well as sincere gratitude to both authors, what follows is their Proceedings article in its entirety;

“Naval Intelligence Must Relearn Its Own Navy”

To best support their warfighting customers, naval intelligence professionals must know the threat and U.S. combat capabilities.

By Commander Christopher Nelson, U.S. Navy, and Eric Pedersen

February 2020

Naval Institute Proceedings

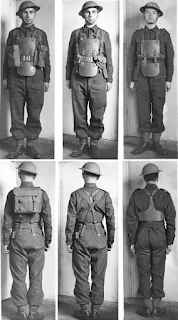

A common saying in U.S. naval intelligence is “We don’t do blue.” It means intelligence professionals do not analyze and report on U.S. naval operations, combat capabilities, or doctrine—blue forces—but instead focus on the adversary: red forces.

The saying is inaccurate, and it obscures a larger problem. “We don’t do blue” was never meant to mean “We don’t need to know blue.” That, though, is how too many in the community have interpreted it for far too long. Today, the sad truth is most naval intelligence officers lack even a basic understanding of U.S. naval combat power.

Factors beyond the basic cultural resistance expressed in “We don’t do blue” have compounded the problem. Including naval intelligence in the Navy’s information warfare community has resulted in additional officer qualification requirements. The naval intelligence officer career path does not consistently and broadly expose officers to U.S. naval combat capabilities. And, most significantly, the United States has spent the past three decades without a peer naval power.

Certainly, naval intelligence officers must focus primarily on the threat (red intentions and capabilities), but they cannot give their operational customers sophisticated threat assessments unless they also have strong foundational knowledge of U.S. military capabilities, particularly naval ones.

Operational commanders need intelligence professionals who can clearly communicate what an adversary can do, is doing, and might do in the future. That will never change. It is and will remain the intelligence profession’s primary purpose. Thus, any conversation about adversary intentions and behavior also must consider how adversaries view U.S. naval power and operations. Without such insights, when intelligence officers stand up and deliver enemy weapon ranges and basic red tactics and doctrine, they are describing only part of the story.

If the community wants to provide sound assessments to the commanders it serves, naval intelligence professionals must develop a good understanding of U.S. naval forces. That will mean going back to basics. The journey will include significant and costly changes to training and processes.

Anecdotal evidence shows that both junior and senior officers lack key knowledge of U.S. naval combat capabilities, platforms, weapons, and sensors. For example, we recently conducted an informal four-question survey with 20 junior intelligence officers: What is an SM-2? What is its range? What is a Mk 48? What is its range? The results were not surprising—disheartening, yes, but not surprising. Only half could identify an SM-2, and only three could identify a Mk 48 (it is a torpedo). Only two came close to the weapons’ ranges, and they were both former surface warfare officers. And these are not niche weapons. The Standard Missile 2 is the Navy’s primary antiair missile fitted on almost all destroyers and cruisers. The Mk 48 is the submarine force’s heavy torpedo for antisubmarine and antisurface warfare.

|

| U.S. Navy Standard Missile SM-2 surface-to-air missile |

|

| U.S. Navy submarine launched acoustic homing torpedo MK 48 |

Recent anecdotal data from the U.S. Naval War College’s Halsey Alfa group suggests that midgrade and senior naval intelligence officers also lack sufficient blue knowledge. Halsey Alfa is a “collaborative student-faculty research effort at the Naval War College that employs military operations research and free play war gaming to examine in detail high intensity conventional warfare.”1 Each year about 15 officers, O-4 to O-5 (predominantly joint warfighters and intelligence officers) form the group to “analyze and war game theater-level contingencies.”2

For two years, Halsey Alfa gave incoming students a 60-question test to establish a baseline of their professional knowledge. Questions covered modern warfighting systems, relevant geography, and basic scientific principles relating to weapons and sensors. The questions included “the range of common weapons like the Harpoon or DF- 21D missiles, the conversion factor for kilometers to nautical miles, the location of Kadena Air Base, the relative frequency of S-Band versus L-Band on the [radio frequency] spectrum, and the difference between a [low-earth orbit] and a [geo-synchronous] satellite orbit.”3 On average, intelligence officers scored 65—barely a passing grade.4

Unfortunately, the Navy does not have any empirical data on officers’ knowledge about their own platforms beyond results from limited testing in their tactical-technical specialties. There are no tests of joint warfighting knowledge at any level in the Navy. From the anecdotal evidence, however, the state of affairs is not encouraging.5

While junior intelligence officers struggle to learn and stay current on threat capabilities, many U.S. Navy platforms will remain in service for their entire careers. Naval intelligence professionals should learn basic blue combat capabilities early in their careers.

It is Not All About Red

To understand the complexities of a foreign navy is a daunting task. Today’s naval intelligence officers must keep up with a massive array of sophisticated threats from Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran, while also understanding the variety of threats Navy personnel confront in the war on terrorism.

The Navy must be ready to execute a wide range of missions anywhere in the world at a moment’s notice. Operating in such a complex environment underscores the critical role naval intelligence plays. Navy leaders must decide what capabilities to buy and where and how to operate with limited resources. They deserve the very best information to guide those critical decisions, and the task of providing that information falls largely to naval intelligence.

Providing quality threat assessments requires understanding an adversary’s mind-set to anticipate his actions. That is a fundamental competency of intelligence. Without understanding what an adversary is trying to accomplish and why, it is impossible to anticipate its moves. In many cases, the capabilities of the U.S. military, and the Navy in particular, have been the primary drivers of adversary development of doctrine, capabilities, and tactics. Adversaries scrutinize the U.S. threat to formulate a response. When the United States fields a weapon, they field a counter; when they field a weapon, the United States fields a counter; and so forth. Attempting to predict adversary actions without understanding their threat perceptions of U.S. capabilities and intentions is a losing proposition.

A deep understanding of U.S. capabilities and limitations raises the intelligence officer’s professional game. First, officers with that knowledge can quickly and accurately prioritize threats. Second, knowledge of U.S. forces enables them to identify adversary weaknesses most vulnerable to exploitation. Third, a complete perspective of blue and red operations helps them discover adversary intelligence successes. During the Cold War, for instance, intelligence officers’ deep knowledge of blue and red forces led them to suspect Soviet penetration of Navy operations. They were later proven correct.6

Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority Version 2.0 states that China and Russia “have been studying our methods over the past 20 years” and “are gaining a competitive advantage and exploiting our vulnerabilities.” It is not difficult to imagine a Chinese or Russian naval officer scoring better than 65 on the Halsey Alfa test. Thus, naval intelligence must not leave overworked operational commanders, staffs, and senior decision makers on their own to sort through threat assessments and apply them to blue capabilities. Instead, it owes them a partner more valuable than they have today: a fully informed intelligence officer to help them arrive at the best tactical and operational solutions.

Build Blue Knowledge

Senior naval intelligence leaders can make several changes to improve the community’s knowledge of U.S. combat power. None will be easy, but each of the following recommendations can help build a basic working knowledge of U.S. naval weapons and capabilities.

Include a robust section on U.S. naval combat platforms and weapons in the information warfare officer’s personnel qualification standard. A primer on U.S. platforms at an early stage in an officer’s career will set a baseline that can be built on over time. Intelligence officers do not broadly cover this material in their careers because there is simply too little time. Officers have to study on their own to learn the warfighting capabilities of the squadron or ship with which they serve, often cramming the material as quickly as possible.

Rotate more intelligence officers to independent deployments of destroyers and cruisers. This would give intelligence officers more time at sea and exposure to a larger portion of the surface navy and, in turn, would provide independent deployers and their intelligence specialists a better understanding of regional threats and adversary naval capabilities. It also would align with Design 2.0 and the distributed maritime operations strategy. In a communication-degraded environment, it will be necessary to push more personnel from intelligence centers to the waterfront.

Create a longer mid-career intelligence milestone course (weeks if not months) with rigorous testing and student ranking. This should include tactics instructors to discuss Navy combat capabilities and a robust discussion on Chinese, Russian, North Korean, and Iranian threats. After the intelligence officer basic course, naval intelligence officer training is an à la carte experience—a course here and there in preparation for whatever job comes next. The community cannot determine if a standard of professional knowledge is maintained. In the aviation and surface warfare communities, mid-level operators are required to demonstrate their knowledge in a classroom, simulator, or when they return to the cockpit. The intelligence community should do the same.

During long maintenance periods, regularly rotate intelligence officers from ship’s company (aircraft carriers and large-deck amphibious ships) to underway units or an established intelligence career course. Currently, intelligence officers are kept on board ships during maintenance availabilities, then expected to develop deep knowledge of regional threats in a matter of months prior to a deployment.

During maintenance periods, officers and enlisted supervise intelligence spaces, process clearances, support maintenance, stand watch, and attend schools and conferences, often in the local area of the ship’s home port. This is important work, but intelligence knowledge degrades significantly during maintenance periods. Workups are intended to get the intelligence department up to speed and ready to deploy. Naval intelligence will soon find that as adversaries modernize and field new weapons, workups will not allow enough time to absorb the amount of information necessary to keep the commanders informed when deployment begins.

Naval intelligence must assess its shortfalls and debate ways to educate intelligence officers on blue forces. Top- down solutions, even the adoption of the suggestions offered here, will not by themselves close the community’s knowledge gap.

The best intelligence officers will do what they have always done—educate themselves the best they can on red and blue capabilities—but the community needs to consider innovative ideas. The next generation must develop and maintain a high-level understanding of red and blue capabilities.

1. See the U.S. Naval War College website.

2. Jim FitzSimonds, Professional Illiteracy, unpublished manuscript (2019). 3. FitzSimonds.

4. Jim FitzSimonds, personal communication, 9 July 2019. Intelligence officer average was 65 (although it was a small number of students). The high score over two years was 76 by a Hornet pilot with intense interest in a broad range of military subjects. Even more disconcerting is the overall class average of 19 out of 100.

5. FitzSimonds, personal communication.

6. Christopher Ford and David Rosenberg, The Admirals’ Advantage (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2005), 192. Former Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence Richard Haver, then an OPINTEL analyst, was concerned the Soviets had penetrated U.S. Navy codes. The arrest of the John Walker Lindh spy ring confirmed his suspicions. Naval Intelligence

Commander Christopher Nelson

Commander Nelson is the Deputy Senior Naval Intelligence Manager for East Asia in the Office of Naval Intelligence in Suitland, Maryland. He is a career naval intelligence officer and graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island.

Eric Pedersen

Mr. Pedersen is the Senior Naval Intelligence Manager for East Asia in the Office of Naval Intelligence. He is a former naval intelligence officer and graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy.

Rather than further boring the reader with having to read both of the previously referenced blog posts, this synopsis should be able to convey the essence of the author’s experiences. It occurred during the course of my dual career as a weapons system engineer/threat analyst, and naval intelligence officer during the preliminary design and subsequent construction of the lead ship of the class, USS Spruance Class Destroyer (DD-963) in the 1970s.

In one of the first design reviews scheduled by the then Navy’s Ships Systems Command (then NAVSHIPS, now Naval Seas System Command – NAVSEA) Program Office for the DD-963 I had the opportunity to review my work to that point with two LCDRs (Lieut-Commanders) from that office. Their names will remain anonymous. I expressed my grave concerns regarding the fact that in 4 out 5 (or 6, unfortunate lapse of memory) of the detailed threat scenarios provided, that the November Class SSN (at the time already it had been in service for 10 years) was able to achieve effective launch range of the stipulated operational Soviet submarine torpedoes, prior to effective own ship reaction/response time, i.e., detection, classification, target designation, target motion analysis, launcher/weapon orders, weapon launch, flight time, deployment, target acquisition and homing. This was quantified by physics and mathematics, no latitude for conjecture or doubt. One of the detailed analyses which we developed, required as a deliverable under contract, was a series of OSDs (Operational Sequence Diagrams) which defined in excruciating detail, own ship, quantified, sequential response through the total threat engagement in each threat scenario. I was personally intimately familiar with these OSDs, I had developed every one.

At that juncture, I exacerbated their dilemma by asking them about how they planned on dealing with the Charlie Class SSG(N)/SS-N-7 challenge? Response; momentary shock and disbelief, then, and I will never forget it, HOW DO YOU KNOW ABOUT THAT!? Not even needing to rely on my naval intelligence background, I related that facts had been conveyed to the civilian ASW community in the NSIA briefings. Needless to say, two very chagrined LCDRs. Honestly I cannot recall how they reconciled the situation, in as much as I was as shocked and angry as they were. At that point in the program they would have had access to the basic intelligence, probably at a level of knowledge between what I then knew as an intelligence officer, and as a weapon systems engineer. I’m not certain what guidance they were ultimately able to obtain, nor at that level how prescient either officer was, but I’m certain all of us agreed the Navy needed a new class of destroyer.

|

| Soviet Navy Charlie I Class SSGN |

|

| Soviet Navy SS-N-7 Starbright (Ametist/4K66) cruise missile |

As the program progressed I became more and more frustrated with the fact that while as a basic weapons system platform the DD-963 was projected to be potentially a highly capable and versatile hull, its capability as an effectively armed combatant was in its initially specified configuration severely lacking.

Independent of either my position at Honeywell or as a naval intelligence officer, I drafted an article, entirely from unclassified open sources, comparing the projected Spruance Class destroyer to the then operationally deployed Soviet Navy Kynda (Project 58 - Ракетные крейсера проекта 58) Class and Kresta I (Project 1134 Berkut) Class guided missile cruisers. In essence the article conveyed that at both significantly lesser, as well as comparable displacements, the Kynda and Kresta I Classes, already at sea, were ton-for-ton (kilogram-for-kilogram) far more formidable warships.

|

| USS Spruance Class (DD-963) original configuration |

|

| Soviet Navy Kynda Class CLG |

|

| Soviet Navy Kresta I Class CLG |

I submitted the article (including a comparative drawing of the ships) to the US Naval Institute Proceedings for potential publication, with a copy to Honeywell management. It suffices that the reaction time of Honeywell was by far swifter, and more directed, than the Spruance could have ever mounted against a Soviet submarine. I was told, in no uncertain terms, that if I was to enjoy continuing employment, I should retract the article. Unfortunately, at that juncture a wife and three small children weighed heavily in the decision, and the article was withdrawn. What was to prove particularly bitter and galling was that within no more than a couple of months the Naval Institute published an article, authored by two active duty navy captains (possibly a career limiting action), which detailed the exact same sentiments. At least it got said. Once again another Don Quixote windmill. Fortuitously, albeit over an un-necessarily protracted period of time, with the integration of the Vertical Launch System, VLS Mk 41, the Spruance Class became a much more capable warship. Albeit two decades later. That was the second bitter pill this author had to swallow. Initial concept presentation to the Navy had been in 1963 (see original model of concept below). The Initial Operational Capability (IOC) for the VLS Mk 41 was in the USS Bunker Hill (CG-52), commissioned September 1986, 23 years later.

|

| U.S. Navy Vertical Launch Missile System VLS Mk41 circa 1986 |

|

Concept model of single cell module

of VLS showing General Dynamics/Pomona

Standard Missile RIM-66 circa 1963 |